When we think about human evolution, the image of hairy, human-like creatures with spears hunting in the open savanna comes to mind. After all, it’s what we have been taught in school and what we have watched in countless movies and cartoons. However, the typical hominin image has been seriously challenged among scholars for a few years: It turns out that humans evolved in tropical forests.

The forest origin scenario not only makes much more sense regarding our similarity to all other apes, it is also supported by genetic evidence! Breaking the savanna origin dogma also has a significant impact on what we know about the human natural diet! But, this major shift in what we know about our origin happened without efforts to correct the perception of the public so far and consequently without making any waves in nutrition.

For quick readers:

While it is consensus that humans are a tropical species and come from an early ancestry of frugivores, our more recent ancestors were thought to have evolved in open, savanna-like environments with much less vegetation, and plant-based foods than in forests. In recent years, a new idea that humans originate in forests challenges the traditional “Savanna Hypothesis.” It basically suggests that our ancestors evolved in tropical forested environments with an abundance of fruits as foods rather than out in the open savannah. This is a real game-changer in the world of anthropology – and in terms of our diet! It shifts the idea that humans are adapted to heavy-meat diets to being a species with diets high in fruits!

Jungle as the human origin

What did our ancestors’ jungle environment look like? Various hominin species seem to have co-existed in a lush green tropical setting instead of hunting in the savanna. This new view is based on new fossil findings and genetic studies, which have painted a very intriguing new picture of the human past:

“Tropical forest clearly represent a key human habitat that can no longer be ignored in the context of deep human history… genetic studies have revealed very deep human roots in Central and West Africa and in the tropics of Asia and the Pacific; an unprecedented number of coexistent hominin species have now been documented, including Homo erectus, the ‘Hobbit’ (Homo floresiensis), Homo luzonensis, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens…”

Scerri, E.M. et al. (2022) ‘Tropical forests in the deep human past’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1849). doi:10.1098/rstb.2020.0500.

Weirdly, this scenario reminds me a bit of the old legends and myths…

And, oddly, the tropical forested environment traditionally has been described as a challenging habitat from which humans have escaped into a “friendlier” savanna environment. This non-sensical view has finally been criticized by researchers: Scerri et al. also stress that those theories have left us with a “biased” view of the past and our ancestors. I couldn’t agree more and would call the forest “escape” theory plain wrong. It’s much more likely that humans had to adapt to a new, scarce, and more challenging habitat when green Africa turned drier (see below). The forest, rich in food sources, was replaced with vegetation-poor savannas, where hunting became more critical to survival.

African savannas used to be green tropical forests

The traditional “savanna hypothesis” is based on the concept that early hominins, such as Australopithecus and Homo species, evolved in response to the challenges of living in open grasslands and developed adaptations like bipedalism (walking on two legs), increased intelligence, and the use of tools for survival. This view has been heavily influenced by the discovery of early hominin fossils in regions like East Africa, which is known for its vast savanna landscapes.

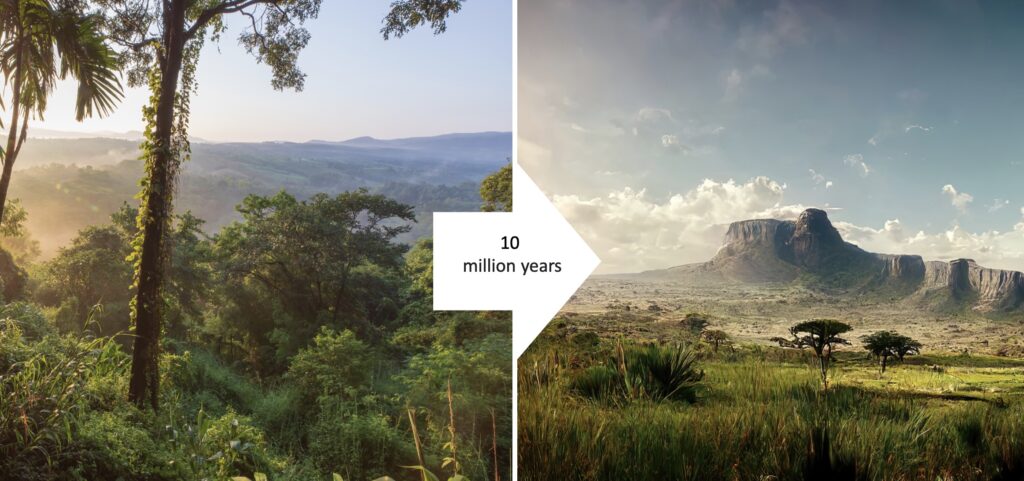

The often overlooked, but well-known piece of the puzzle, is that the East African savanna used to be more lush and green, more of a tropical arboreal type biome:

“The landscape of East Africa has altered dramatically over the last 10 million years. It has changed from a relatively flat, homogenous region covered with mixed tropical forest, to a varied and heterogeneous environment, with mountains over 4 km high and vegetation ranging from desert to cloud forest” (Maslin et al, 2014)

Forest ancestry reveals a lot about the natural human diet!

One of the most significant implications of the “forest origin” of humans is certainly rethinking our natural diet. Depending on the biome type, there are different amounts of plant foods available. Species with a diet based on fruits can only be sustained by the food sources in tropical forests. If we, indeed, have evolved in African forested landscapes instead of a savanna-like biome, it fits that humans are frugivores.

If humans evolved in tropical forests, then we have evolved in an environment full of fruits. This stands in contrast to evolving in a dry, scarce environment, where hunting is a survival strategy.

Food Sources in the savanna: tubers, hunting for meat, greens, seasonal fruits, nuts. Fruits are just an occasional addition to cooked foods.

Food sources in tropical forests: highly nutritious fruits in abundance all year, greens, nuts, tubers, and meat. highly frugivorous diet is possible.

There is no doubt that humans have become hunter-gatherers as a cultural response to leaving their lush forested habitat later in our past. But our evolutionary development unfolded in tropical forests, shaping our traits related to diet. This past has vast implications for understanding what type of diet we have evolved to eat.

Diet changes with climate, habitat, and food availability. Humans are more flexible in terms of diet than all other species because of the ability to manipulate food sources, to turn inedible matter, into edible foods i.e. including hunting and cooking (Luca et al., 2010) And while these intelligent skills enable(d) us to survive in cold or dry climates, it does not mean that those foods are optimally suited for the human body. Biologically we are still adapted to a diet high in fruits, which is reflected in our characteristics as frugivores.

We originated in Africa and migrated into colder climatic zones using cultural and technical skills, rather than biological adaptations.

What about upright walking, climbing, and a big brain?

Old dogmas never go down without a fight. New theories, which have the potential to disrupt a field of research, often encounter the most rigorous skepticism. Some of the most prominent arguments against the “forest origin” are upright walking, climbing, and big brain evolution:

Does terrestriality disprove that humans have evolved in tropical forests? No. While walking upright and living on the ground are major arguments for the savanna theory, these traits could also have evolved in a more forest-type environment than in an open savanna environment. Takemoto (2017) analyzed this question as a response to emerging evidence that human ancestors evolved in wooded environments. By studying chimpanzee populations he could conclude that terrestrial living indeed can evolve in forests.

Do climbing skills disprove that humans have evolved in tropical forests? No. While humans do not live in trees, we still have the anatomy to be good climbers if the skills are trained since childhood: “Human hunter-gatherers who climb trees regularly achieve extraordinary ankle dorsiflexion equivalent to that seen in chimpanzees during climbing through soft tissue adaptations” (Drummond-Clark, 2023)

Do the large brains of humans disprove that humans have evolved in tropical forests? No. It’s been a strong dogma that large brains arose from meat-eating or complex social behavior. However, brain size has now been attributed to fruit foraging. (DeCasein et al. 2017)

Comparing apes and humans to understand our origins

The theories around our evolutionary past are not written in stone. Our understanding of human evolution keeps evolving itself, mostly because most of the time, studying the past is not an exact science. Luckily, a comparative approach to living closely related species to humans is being embraced by research in these newest “forest-origin” hypothesis:

In a brand-new paper called “Bringing trees back into the human evolutionary story: recent evidence from extant great apes”, Drummond-Clark suggests, based on fossil evidence and comparative studies of great apes that “whilst a shift to exploiting open habitats catalyzed hominin divergence from great apes, adaptations to arboreal living have been key in shaping what defines humans today, in counter to the traditional savannah hypothesis.” (Drummond-Clark, 2023)

These latest discussions around our origin finally line up with the frugivorous characteristics we find in humans today, such as the loss of functional vitamin C genes, trichromatic color vision, dental structure, the love for sweet and sour, and many more.

Those characteristics are found in all apes – our fruit-loving closest relatives. Moreover, it’s no secret that our early ancestors were frugivores, too:

“The diet of the earliest hominins was probably somewhat similar to the diet of modern chimpanzees: omnivorous, including large quantities of fruit, leaves, flowers, bark, insects and meat.”

P. Pobiner, Nature Education

“Plants are what our apey and even earlier ancestors ate; they were our paleo diet for most of the last thirty million years during which our bodies, and our guts in particular, were evolving… and for tens of millions of years those (our) ordinary guts have tended to be filled with fruit, leaves, and the occasional delicacy of a raw hummingbird.”

R. Dunn, Scientific American

Our ancestors were frugivores, our relatives are frugivores, we look like frugivores… are we frugivores? Sometimes, taking a step back helps to get a bigger picture. While we cannot know exactly how our evolution unfolded, we can look at our species today and study the traits and adaptations that we actually carry around. And it’s not hard to see that we share so many traits with all other apes. So why should our natural environment be so different from our tropical cousins?

For this to make sense, we need to be aware that cultural adaptation masks our biological adaptations. We have overcome the limitations set by nature largely with culture and technological tools – not by evolutionary changes. So, to understand in what environment we have evolved, we might ask: In what type of habitat can humans survive without manipulating the environment by heating, cooking, etc.? In what type of environment can we live with our biological set-up alone, like other species?

Most of us would agree that we feel best in the tropics, with an abundance of fruit-bearing trees fruits! This means our natural habitat and ecological niche still lies in tropical forests. Not savannah-like environments.

Our closest relatives are frugivores. Our ancestors were frugivores. We look like frugivores. Are we frugivores, too?

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication: If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

Conclusion

It is consensus that humans come from a frugivorous ancestry. Highly frugivorous species depend on tropical forests as their food-providing, natural habitat. Apes – our closest living relatives – are all still highly frugivorous and depend on tropical forests for food. Moreover, modern humans share many anatomical and physiological adaptations related to diet and specializations in fruit-eating with them!

The “forest origin” is one more argument that backs up that our natural diet is high in tropical fruits, nuts, and greens, similar to the diet of chimpanzees. The evolutionary diet of humans is frugivorous and challenges the view of humans having adapted physically to a hunter-gatherer diet, which is high in cooked foods and meat.

References

- Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. (2014) ‘Is the “Savanna Hypothesis” a dead concept for explaining the emergence of the earliest hominins?’, Current Anthropology, 55(1), pp. 59–81. doi:10.1086/674530.

- Drummond-Clarke, R.C. (2023) ‘Bringing trees back into the human evolutionary story: Recent evidence from extant Great apes’, Communicative & Integrative Biology, 16(1). doi:10.1080/19420889.2023.2193001.

- Scerri, E.M. et al. (2022) ‘Tropical forests in the deep human past’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1849). doi:10.1098/rstb.2020.0500.

- Takemoto, H. (2017) ‘Acquisition of terrestrial life by human ancestors influenced by forest microclimate’, Scientific Reports, 7(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05942-5.

- DeCasien, A.R., Williams, S.A. and Higham, J.P. (2017) ‘Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality’, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(5). doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0112.

- Maslin, M.A. et al. (2014) ‘East African climate pulses and early human evolution’, Quaternary Science Reviews, 101, pp. 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.06.012.

- B. Pobiner, Evidence for Meat-Eating by Early Humans (2013) Nature news. Available at: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/evidence-for-meat-eating-by-early-humans-103874273/ (Accessed: 29 May 2023).

- Dunn, R. (2012) Human ancestors were nearly all vegetarians, Scientific American Blog Network. Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/human-ancestors-were-nearly-all-vegetarians/ (Accessed: 13 September 2023).

- Luca, F., Perry, G.H. and Di Rienzo, A. (2010) ‘Evolutionary adaptations to dietary changes’, Annual Review of Nutrition, 30(1), pp. 291–314. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141048.

- D. P. Watts, K. B. Potts, J.S. Lwanga, J. C. Mitani, Diet of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda, 2. Temporal Variation and Fallback Foods. American Journal of Primatology. 74, 130–144 (2011), doi:10.1002/ajp.21015.

Add Comment